Step 10. Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly admitted it.

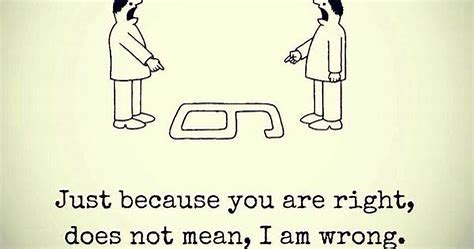

Today we’re going to take this right/wrong thing to a whole new level. We’re going to give up the need to be right and conclude that the only “right” version of what we’re looking at together is what the other person actually sees. In other words, I’m going to give up my need to be right for the more noble cause of understanding the other person’s perspective.

Being right is narcissistic. It’s all centered around me. “I’m right; you’re irrelevant.” It’s also way overrated. It’s forcing everyone around me to see what I see, when, in fact, my life could be greatly enriched by seeing things from everyone else’s perspective.

In the cartoon above, both people are looking at the same number and seeing it from different perspectives. These two people could argue until they are blue in the face that they are looking at a “6” or a “9” when, in fact, they are both right. It’s all about perspective. However, you don’t get that perspective until you are willing to leave your point of view and listen to or look at someone else’s.

My wife is dyslexic. She often sees things upside down. She could be looking from the “6” point of view and actually seeing a “9.” She talks about this as an advantage — how she can play chess and flip the board in her mind’s eye and see what the other person sees. Would that we could all be dyslexic in this manner. So what if I prove I am right? All I’m saying is that my perspective is the only one there is. It’s limiting. I’m limiting my reality to only what I can see. But what if someone sees something I don’t see? Then I will be expanding my reality to see from their point of view. This is what it means to climb into someone else’s shoes. You learn to see what they see. You broaden your perspective. You can see why being right can be so overrated.

Being willing to admit we are wrong is a huge attitude change and it opens up a host of other possibilities. Os Guinness writes in Zero Hour America: “Instead of excusing ourselves and rationalizing as we humans usually do, wrongdoers who confess voluntarily go on record against themselves. Whenever someone says, ‘I wronged you,’ they are shouldering the personal responsibility for what they did and clearing the person who was wronged of any part in the wrong done to them. Confession is both damning and liberating.” (p. 139)

Remember this all comes out of continually taking a personal inventory of ourselves. It’s that inventory that enables us to become aware when we were wrong or have wronged someone. And if we take that inventory from the heart we can better avoid the excuses, rationalizations and justifications that always crop up in our heads. The heart is where we hurt when we realize what we have done.